Mass & Cass: a look back as we move forward

Doubling down on our public health and housing approach with a three-part plan to boost public safety for patients, workers, and residents in the area

Since my very first day as mayor, the most pressing and complex priority has been addressing the humanitarian crisis concentrated near Mass Ave and Melnea Cass Blvd (“Mass & Cass”)—dozens of people living on the street in the grips of substance use, mental illness, and homelessness.

In just over a year and a half, we’ve made solid progress on a situation that has been many years in the making. But in a world that craves quick fixes and deserves urgent action, it’s not enough to move in the right direction—our job is also to be clear about what we’re doing, why we’re doing it, and how our efforts are working or falling short. So today as we file an ordinance that’s part of a planned phase change at Mass & Cass, it’s important to share the bigger picture.

How did we get here?

The story of Mass & Cass as we know it today can be traced back to October 8, 2014, with the sudden closure of the Long Island Bridge, which had been the access point for daily buses traveling back and forth from near downtown Boston to the region’s largest emergency shelter (about 500 beds) and several long-term recovery programs (about 300 beds) located on one of the Boston Harbor Islands owned by the City of Boston. Built in 1951, the bridge was nearing the end of its useful lifespan, but with ongoing disagreement about which level of government should pay to replace a bridge to a City shelter that served a regional and even statewide population, the structure deteriorated to the point of serious safety concern. On that Wednesday nearly nine years ago, the City shut down the bridge, displacing hundreds of vulnerable people to the mainland with just three hours’ notice.

Today the rooms and spaces at the Long Island public health campus still look eerily frozen in time, with papers and clothing scattered all over, left behind when everyone boarded a bus for the mainland for the last time with all they could carry. At the time of the shutdown, I was a freshman City Councilor living in the South End, and I remember the chaos and confusion as neighbors tried their best to help when hundreds of cots were set up as emergency sleeping space in the South End Fitness Center gym, then watched as what was promised to be a temporary new shelter built at Southampton Street and recovery services relocated near Boston Medical Center became permanent parts of the neighborhood.

As housing costs soared in Boston over the next several years and the number of fatal opioid overdoses more than doubled across the country, more and more unhoused community members found their way to living in a growing encampment outside the Southampton Street shelter and nearby services. In August 2019 the City directed law enforcement to break up the encampments through nightly sweeps, but without low-threshold housing options or storage for belongings, it felt like an exercise in cruelty and displacement that scattered everyone until the crowds were back again that summer.

By the summer of 2021, there were hundreds of people living in tents and fortified structures set up on Atkinson Street, Southampton Street, and all around the Newmarket Triangle. In October 2021, then-Mayor Janey signed an executive order establishing protocol for tent removal and began clearing some of the encampments with the requirements that there would be a list of shelters distributed to each individual before their tent was removed, storage for personal belongings, and 48 hours’ notice. But many still had nowhere to go.

Building a public health & housing infrastructure

In addressing any challenge that Boston faces, my goal is for our administration to deliver real, lasting impact, not just apply band-aids to get by for another news or election cycle. At Mass & Cass, the same sweeps had been conducted over and over again, without meaningful change. After I became mayor in November 2021, we paused the tent removals to build a new approach.

In early December 2021, our public health teams surveyed every resident in the encampments to understand each person’s history, medical needs, and housing situation. Nearly everyone was living with substance use and medical conditions, many for several years in the Mass & Cass area. The vast majority of people described how existing shelter options felt out of reach for them, because of sobriety requirements or strict time windows to claim a bed for the night, or because there were no options for couples who wanted to stay together in a shelter system with only single-gender spaces. In total, nearly 150 people said they had no other housing options where they would feel safe. Most were living not in simple tents, but fortified structures made of wood pallets, tarps, and construction materials, with propane tanks to keep warm that were causing fires every few days.

Over the next several weeks, we worked around the clock to create and staff six sites in Boston with individualized housing units where residents didn’t just have their own private space, but access to wrap-around care—from medical and substance use treatment, to case management and housing search supports. The nearly 200 low-threshold supportive housing beds we created, including two sites with designated spaces for couples to stay together—were the first of their kind anywhere in the city or state. On January 12, 2022, everyone on our list moved to a safe, warm home at one of these sites, and we cleared away the empty structures and materials from the encampments. It was an intensive operation with detailed protocols for each department and agency to participate in the outreach, transport, storage of belongings, and confirmation that the structures were abandoned. With just about every front loader and piece of equipment available, our Public Works team moved fast to clear the street as each structure was emptied and checked off. In total, they collected 44 tons of debris that day.

Two weeks later, a record-setting blizzard blanketed the city, and it was a tremendous relief that the streets were completely empty, no longer home to hundreds of people who would’ve been at risk of losing their lives in the bitter cold.

Our coordinated response approach at Mass & Cass has been transformational, putting hundreds of people on the path to recovery. Today we have a solid public health and housing infrastructure as more people move on from the transitional low-threshold housing units to permanent housing and free up spots for those next on the list. We’ve worked with emergency shelter providers to address concerns about privacy and storage so this critical system can serve everyone. Outreach to connect people to services from the Boston Public Health Commission and partner organizations has been expanded to run not just during the day but also overnight, and we’ve created a family reunification program to help people find stability from their support networks. The Boston Police Department’s Street Outreach Unit works to maintain public safety with particular training on mental health and substance use. Our Public Works Department administers nearly thirty street cleanings per week to ensure sanitation, including deep cleaning multiple times per week requiring everyone to remove their tents and tarps and shift to a different location while the power washing takes place. All of our agencies check in every morning at 8:45AM to review any incidents or needs highlighted overnight and make a plan for outreach to specific individuals over the next day.

Since January 2022, more than 500 people from the Mass & Cass area have been served at these low-threshold supportive housing sites, and 149 people have achieved the stability, health, and recovery to move on to permanent housing. But the street hasn’t remained empty—new people in need of services continue to arrive from outside Boston and Massachusetts, and crowds continue to gather in the warmer months with increasing concerns about drug trafficking, human trafficking, violence, and other criminal activity undermining our outreach and services.

It has become increasingly difficult for Boston Police to do their jobs, because although we no longer have structures fortified with wood pallets due to the initial clearing and daily street cleanings, tents and tarps still pop up after each cleaning, and they make it challenging to interrupt criminal activity that’s hidden from view. The Boston Globe reported yesterday that a City Councilor shared that she went to Mass & Cass for the first time on Friday evening and was mugged, with the existence of tents playing a role in making the retrieval of her property more complicated. I’m very thankful that she is safe and that BPD officers on scene were able to help get her belongings back that night. We hear from our public health outreach workers and City staff in the area that incidents of violence connected to the tents and tarps occur on a daily basis, and we need to take action to keep our communities safe.

Ready for a phase change

As the proportion of individuals in need of low-threshold housing has dropped, the number of individuals at Mass & Cass who have housing but are engaged in drug trafficking, violence, or other criminal activity has grown. In recent weeks, some of our longstanding community partners have withdrawn their outreach staff from the Mass & Cass area due to safety concerns. With our housing and public health infrastructure in place, and as the state begins to expand low-threshold housing sites in other cities based on Boston’s coordinated response model, we must address the public safety concerns that are undermining our outreach and services for public health, housing, and recovery.

We’re ready to move on a three-part plan for a phase change at Mass & Cass:

An ordinance to boost public safety by giving BPD the authority to remove tents and tarps immediately. Mass & Cass has been on BPD Commissioner Michael Cox’s priority list since he started in his role a year ago, and having taken this time to fill key posts in the department and assess the seasonal challenges in this area, he and his team are ready to implement, but they’ve made it clear that they need the authority to move quickly, not just with a 48-hour notice period that makes it difficult to match the immediacy of public safety issues and drug trafficking concerns in the area. The ordinance is carefully tailored to protect the rights of those who need housing and services, with clear requirements for available and accessible shelter, as well as adequate storage for personal belongings.

Expanded low-threshold housing and shelter capacity. Our goal in removing tents is to eliminate the violence and criminal activity shielded by the encampments, so that our teams can safely and effectively reach those who need housing and services. Our ongoing surveys and outreach find that a relatively small number of people are living in tents at Mass & Cass because they have no other adequate housing options. As we implement this major phase change, we are creating additional beds to absorb the disruption and ensure that no one is stuck with nowhere to go during this transition. Our shelter partners are creating additional beds, and we will temporarily house up to 30 people who are already working with our teams on case management and housing search at the Boston Public Health Commission’s Miranda-Creamer Building nearby. Although neighbors have been concerned about adding more social services infrastructure in this same area (and even closer to the residential neighborhood), we must create overflow to absorb the impact of this significant change, and will close down the site as soon as all the individuals have moved on to permanent housing or one of the City’s low-threshold sites; these spots will not be backfilled.

A coordinated response operation to return Atkinson Street to standard roadway usage and deliver outreach services citywide to prevent new encampments in other neighborhoods. Boston Police will be ready to deliver the presence and coverage that our public health workforce has been asking for—including 24/7 presence to implement the ordinance on Atkinson Street and in the Mass & Cass area, as well as coordinated response mobile units with public health and public safety staff conducting outreach citywide to ensure no additional encampments form in other neighborhoods. All of this will be run from a central operations post in the area, where all agencies and key community partners will have leadership in one place to adjust plans in real time, ensure close communication, and continue to refine our operations.

Some of the quick soundbites about the above have sparked questions about why we’re returning to failed strategies of sweeps, or whether we’re admitting failure in our approach to date and now changing direction. Never before in the decade of struggles at Mass & Cass has this scale of public health and housing infrastructure existed alongside detailed plans and leadership from Boston Police to ensure that public safety efforts are coordinated, comprehensive, and responsive in real time within the parameters of the proposed ordinance. It is precisely because of the progress from our public health-led approach that we are able to take new steps with our partners to stabilize the area and make the transition to a safe and effective outreach system.

It’s our hope that the City Council will act with urgency to pass this ordinance so that our preparations and implementation can happen before temperatures drop again in late fall.

Boston in the national context

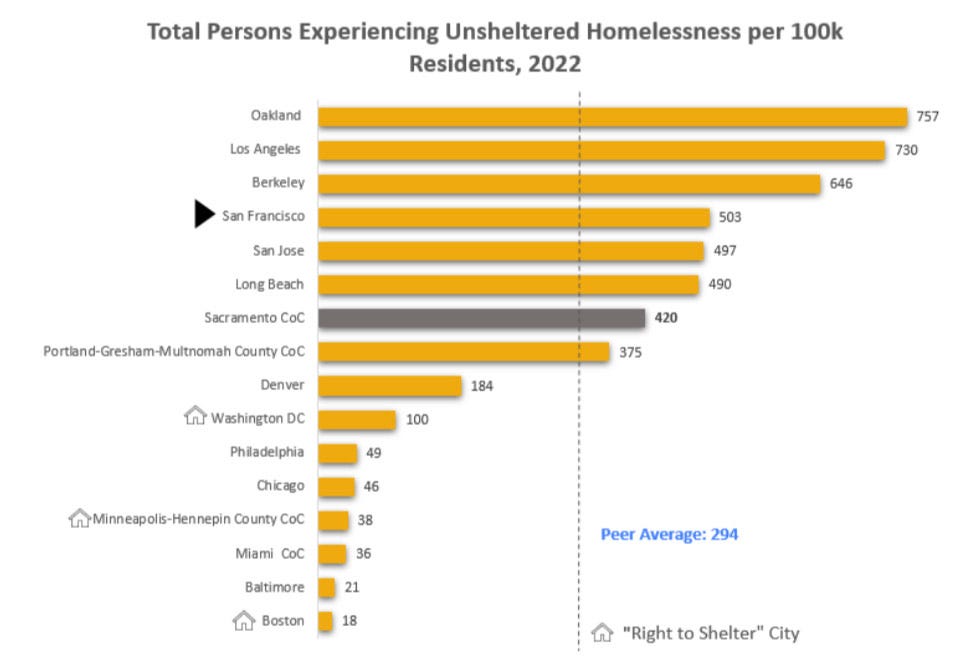

Our coordinated response approach has already been held up as a national model because—while every major city in America is grappling with this issue—few are tackling the crisis at its roots. Each year, large cities across the country conduct a Point-in-Time census count of the unsheltered population on a single night and report their data to the U.S. Department of Housing & Urban Development (HUD). Boston’s 2022 census counted 119 individuals sleeping on the street. For comparison, Philadelphia counted 788, San Francisco listed 3,554, and the City of Los Angeles reported 28,458 people. This chart from San Francisco’s 2023 benchmarking report shows the population of individuals experiencing unsheltered homelessness scaled to each city’s population.

With major steps forward in the permitting process in recent weeks, our plan to address the crisis at Mass & Cass has come full circle to where the problem began: to meet the level of need we’re seeing—at a scale and with the quality that our residents deserve—we are accelerating our plans to rebuild the Long Island bridge and public health campus. We’ve begun coordinating with healthcare and recovery providers, including all the organizations who were previously serving patients on Long Island, in order to plan for the delivery of coordinated services, treatment, and workforce development opportunities to enable not just recovery, but long-term health and success. As Boston continues to be the center city serving residents from all across the Commonwealth and beyond, we are looking to create a regional resource that will transform lives and demonstrate, once again, just how much is possible when we commit to tackling root causes and building systems that serve everyone.

A farrago of self-flattering lies and misrepresentations. I will pick out a small number of them:

1) The crisis at Mass & Cass did not start when Walsh closed the bridge in 2014. Barbara Ferrer of Boston Public Health laid the foundation for the crisis when she stopped sending vans with clean needles all around the city and centralized needle distribution in one spot, on Albany Street near Mass Ave. Drug users had to come here (yes, I live around the corner) and drug dealers followed, and more drug users came from across the state and the Mass and Cass area became an open-air drug market. Closing the bridge made the problem more visible, but there were news programs (find them on youtube) about what they called Methadone Mile before the bridge came down. Barbara Ferrer moved on to Los Angeles Public Health and used the same Harm Reduction playbook to start an even bigger open-air drug market there.

2) Michelle Wu opposed reopening the bridge to Long Island for as long as she was a city councilor. She only adopted it after she became mayor because she, like Martin Walsh, found it a useful distraction from her disastrous policies.

3) Within a week of taking office, Michelle Wu cancelled Kim Janey’s plan because it did not meet the approval of the ACLU and began casting about for a new plan. While she diddled, two people froze to death. Yes, she got the tents down before the blizzard, but those tents came back and stayed up last winter because we were told the residents were safer and more comfortable that way. Now, she is telling us that the tents must come down before the winter because they will not be safe or comfortable.

4) At her press conference on January 10, 2022, just before tents came down Mayor Wu promised as her immediate strategy to clear the encampment and house those in tents, continue public health outreach, repair and clean the streets, and that “the Boston Police Department will ensure a safe environment for residents, businesses, and individuals accessing care.” Twelve months later, she boasted that the situation was 80 to 90 percent better to her Amen Corner at WBUR. Eighteen months later, the streets are neither clean nor repaired, the BPD has not been allowed to ensure a safe environment, and the tents are back, less numerous but much larger: in terms of square feet of tented space, it is a draw. There were only 150 people on the street when the tents came down, now there are more than 200. And that is after, according to Cullen Paradis of the Boston Guardian, she spent 40 million dollars in the last year and a half on these programs.

5) Yes, 149 people from the street are now in permanent housing, but not because they have achieved what she calls “stability, health, and recovery.” The Housing First approach rejects making housing contingent on treatment, and so the vast majority of those people are still using drugs. How is that progress? If they come back to Mass and Cass to buy drugs, they are still supporting the open-air drug market. If they buy locally, they are destabilizing the neighborhoods they are now living in.

6) The neighborhoods and business community has come up with a much better plan, Recover Boston, that would focus on recovery not the perpetuation of addiction. Mayor Wu does not like it because it did not emerge from the same experts at Boston Public Health who created the crisis in the first place.

I appreciate this more in-depth discussion about the situation direct from the Mayor, as well as the detailed comments of residents. As a Boston resident not in the vicinity of Mass and Cass, this is very helpful to understanding it more fully. I hope that this time we really have a handle on the immediate issues AND root problems.